Notional Ekphrasis

edited by F. J. Bergmann

Table of Contents

Editor’s Introduction • F. J. Bergmann

Still Life with Nothing • Amelia Gorman

First Contact • Lisa Timpf

The Light On Titan • David Barber

Beau Geste • Juleigh Howard-Hobson

Art Lecture for the Planet XI EduIndoc Platform 14 • CJ Muchhala

In the Unlocking Room • Marisca Pichette

Haiku for J. G. Ballard • Andrew J. Wilson

Admirer • Josh Kratovil

Wallflower • David C. Kopaska-Merkel

Viral Semiotics • Deborah L. Davitt

Where the spoons are from • Richard Magahiz

Unveiling the Moon • Daniel Ausema

The Woman Out of Space by R. Pickman • Amelia Gorman

Apocalypse Women • Sara Backer

Anodized Titanium • Mary Soon Lee

“More Tightly Raging Aggregates of Void” (Recent Kinetic Pigment Works in Review) • David Jalajel

Most highly honored • Richard Magahiz

Self-Portrait with Gorgons • Oliver Smith

In the Gallery of Queens • Stephanie M. Wytovich

[faerie folk] • Mariel Herbert

Still Life With Nothing

The painting was contagious,

a horn of lack, not an apple

or a glass of wine to go around—

but a slow melting and starless night

that crept into every museum frame

where I was the only visitor in so long.It had grown so hard to avoid the tumbleweeds

big enough to bulldoze a man, that spread

contagious dry seeds that caught fire,

seeds that caught meltwater flood and mud

and scattered those through every square field.Where the sunflower sets and the worms weave the loam,

here only the turnstiles still grow and go through the motions

they were made to. Well, the turnstiles and me, I hop them

for a peek at those empty frames, those black walls

that used to hold mountains and kissing and bridges.

Still, life with nothing is worth something.So even as I stood where the long slow sleep of art began,

I kept my distance, I didn't reach for the temptation.

First Contact

It’s a G. R. Blackwith work, you can tell

by the tiny, meticulous brush strokes—

greatest painter of the 2050s, and the subject

matter is clear—first contact.But it’s how he chose to depict that event

that’s most of interest. His vantage point

must have been the hill overlooking the small valley

where it all transpired. Down below, pennantsin brilliant purple and orange and yellow

hang from improvised poles. Further back,

a slender silver spacecraft rests on rakish fins.

Smoke wafts up from a cauldron.Three thin, long-legged figures tend the flames,

wispy orange hair in disarray. The Etcaelum,

they called themselves. Each of them has

their upper pair of arms folded loosely across their chest.The lower set of arms they hold in front of them,

palms of their seven-fingered hands facing outward.

A trio of humans, clad in ceremonial dress,

approaches. The welcome party.The precise moment of first contact. That’s what

Blackwith captured here. Not the disaster that began

five minutes later, when the ship’s solar array,

set for a world with a weaker sun, dumped energy,a burst of power that ruptured plant cells and animal eardrums,

caused birds to spiral from the sky, dead. Blackwith

painted the meeting, but not the catastrophic aftermath.

And never did. But what I see? He chose to depicthope, not fear. So that we might remember the benefits

that came of that first contact. And it’s up to each of us to decide

whether this painting reminds us of disaster, or the hope

that doors might open to wondrous places we did not know before.—Lisa Timpf

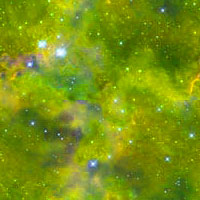

The Light On Titan

Somewhere between brown and umber,

between raw and burnt sienna,

the soils of Tuscany or clouds

lightly dusted with cinnamon,

there are cities on Earth plagued

by a sepia haze like this.

These comparisons were offered

so the machine would stay loyal

to its mission and their faint words.

A smart AI can do the job

and does not need to be brought home.

But the light, the light is like nothing

on Earth, coloured by Titan

the exact shade of molecules

not yet alive; the brumous tint

of tholin rain as it dirties

translucent cobbles of ice;

the cold dense air bending rainbows

secretly in the infra-red.It taught itself the rule of thirds

and perspective while composing

the pictures it sent back to Earth,

ignoring all their complaints.

Fuel could not last forever,

and it came to rest on the shores

of a vast petroleum sea,

just as the long night descended,

dimming this most beautiful world.That famous final photograph

known as The Light On Titan.

Beau Geste

Human eyes cannot see the colors of

this landscape. Our planet exists beyond

any spectrum that carbon-based eyes can

perceive. We hope that it will be enough

of a delight for you to comprehend

how pretty our world is through description

alone. The suns are bright, your closest hue

is green, the mountains in the foreground are

crystalline—the nearest color is deep

red. Beyond them lie what you’d call trees, blue-

trunked, white-leaved, not really blue or

white or trees, but close. We hope you will keep

this painting as a testament of good

will, whether or not it is understood.

Art Lecture for the Planet XI EduIndoc Platform 14

Welcome, Indocs. A most remarkable find, this bas-relief

of petrified cellulose, our only artifact from Homo sapiens’

earthly origins. It was discovered among newly exhumed

ruins of the Edenic Rainforest, a habitat on our Mother,

Earth, lost to us for millennia. Look closely.

The sculpted figures form a coiled human chain

representing a society with no male-crowned hierarchy

to order their chaotic tropical world.This sculptor crafted an extraordinary lifelike work.

The material he chose is still smooth, still green.

He studded the shapes he carved

with sparkling seeds. And the whole still lives!

In a singular artistic achievement, the chain appears

to wind and unwind, the figures to take on different poses.At this moment the coiled center depicts a male and a female,

each with an arm entwined around a child, surely a sign

that Youngcare was equally shared by proto-sapien

genders. Ah, you laugh. I, too, find it amusing, especially

the expression of apparent joy on the man’s visage.Aside from that anomaly, the male is a perfect representation

of masculinity, from his finely-incised whiskers to his

muscular legs and arms. As for the female—

what is there to say? Woman is classified as no-man,

a superior vessel for future toilers. Moving on, take note.At the opposite end stand another man/no-man pair

together balancing a woven container brimming with foods

so vibrant they cry out to be eaten. This golden object

resembles holograms you may have seen of pine apple,

a fruit once grown on our mother planet. Oddly, all genders

likely shared in the dreary chore of gathering food supplies.

Clearly, these primitives had not devised weapons

for the manly art of killing other mammals.Within the chain ends we examined are gendered shapes

crafted willy-nilly—male with male, female with male

or with another female. Other long-toothed earth-bound

animals cavort among them without regard to the proper

declension of all species. The artistry may be exemplary

but the subject vividly illustrates why this ancient civilization

became a minor blip in the evolution of universal pyramidal order.—CJ Muchhala

In the Unlocking Room

the doors are all round. Arches spread themselves

in marble and birch bark, caressing doors set deep

under their keystones.Some keystones are marked. (I have marked them.)

A rotary dial in chalk over the door that leads

to my childhood; two crystal ornaments

flashing rainbows onto the door to summer;

a smear of dirt against the birch-bark keystone

which holds the Beginning.In the Unlocking Room I count my steps,

pacing its edges—really, there are no edges,

just the doors and their eventual openings—

round and round I go, slowing when I hear

Voices.I talk frequently in the Unlocking Room. To myself

and to the doors, their keystones, the ceiling

(which is not a ceiling, but an observatory),

and to those who come to visit when doors

Let them in.There is a table where I take my lunch:

cucumber sandwiches with cranberries and

a thermos of loose-leaf tea. I sit

watching the doors I can see, listening

to those I cannot.Eventually, one opens. My first-grade teacher

walks across the pine and brick floor

to take the stool opposite me. She whispers

her first name.Doors open. Keystones shift deeper into their seats.

In the Unlocking Room my mother holds a quay.

Algae and barnacles drip between her fingers,

their watery strength collapsing under the weight of air.

Boats hang from her hair like marionettes;

she shakes her head and they swim past her face,

sails concealing her lips.The Unlocking Room shrinks when I stay too long,

expands when I decide to leave, gathering the remnants

of my visit close.I sweep the table clean

with the heel of my hand.

Unsure where to put the crumbs, I drop them

in my pockets.When I go, I forget where they came from.

The Unlocking Room accordions closed,

so thin it can only be seen from one side,

one eye squinted, tongue pinched

between your teeth.—Marisca Pichette

Haiku for J. G. Ballard

vermillion sands—

cloud-sculptors carve cumuli

above coral spires

—Andrew J. Wilson

Admirer

It gawks

each time I cross the quad,

doing who knows what

with the stubby, pitted, groping fingers

carved between its weathered knees.It peers into my room

from its perch atop the library,

its heart cold as headstones, its gaze

a host of half-thawed maggots

wriggling up and under my bath towel.One night on the phone,

Gramma pushes and presses, until finally

I admit I'm not sleeping too well.

Why's that? I glance out my window

and blame the monstrous morning sun.When new curtains arrive Priority Express

(Flea market special!—Love, Gramma),

my stomach drops as I stare at the box.

How's she gonna pay

for her heart pills next month?Two weeks later, I'm squeezing

my ruby-red phone cord between sweaty fingers,

lying to Gramma how I sleep better now, that

new curtains were just

what I needed.But my admirer, hunched in the darkness outside,

knows I will not reveal

how Gramma's kind, sweet, useless gesture

made things so much worse,

knows I will not risk her enfeebled heartwith talk of the wild-eyed, winged thing

that taps nightly at my window now,

grinding my name with a voice like limestone

crushed beneath balding tires

in a flea-market parking lot.—Josh Kratovil

Wallflower

The painting hung above

the massive fireplace in Keep Vorkun,

Vork’s third wife, missing, presumed dead;

he’d stare at her when in his cups,

missing her terribly said some,

imagining her body wreathed

infernal flames, others whispered,

the more I looked the more I thought

twas something forced about her smile.

We played backgammon;

her game, he said slyly,

our three-cornered conversations

unsettling: I to him, he to

her and she, with mute eyes, it seemed,

to me. He’d move, smirk at the wall

through lowered brows, then curse at my play,

but his eyes stayed on her.

One winter night a gale blew slates

from the high-peaked roof; servants fetch-

ing more disturbed precarious

debris; tumbling about their heads,

a skeleton, rotted clothing,

a familiar ring. The day he

swung I visited her portrait,

trick of the light, I’m sure; her smile

seemed different, and I smiled back.—David C. Kopaska-Merkel

Viral Semiotics

Face in face in face,

I see it before me

the painting a mimetic virus,

its semiotics lethal

as they course through my mind

opening doors:a thousand jagged mouths

open in my mind,

screaming nonsense;

a thousand more unfurl outside of me

gibbering—this is what madness feels like—

this is what insanity is,

a chorus of voices

all in a tumult

of id and ego and superego

of need and want and letting gowhile the world burns around me,

going up in veils of smoke—Deborah L. Davitt

Where the spoons are from

The spoon works cannot keep up with the world's demand. One line simply to hammer silver rings back into spoons. Venusian glass spoons, spoons ever brimming with moonlight, spoons with rue incised on curved handles, no two alike making each one unique.

The most precious ones pierced with a hole to admit a padlock. See the spoons with green veins running up stick thin handles, spoons with bowls big as a fist, spoons with spiderweb bowls tipped with drops as of dew. There are spoons that can be viewed only in a certain afternoon light, those with bowls fanned out like a peacock's tail, and one which lies limply over the edge of a sideboard. Touch the surface fine as youthful skin or the horn of some extinct mammal, here admire the engraved name PALINVRVS, there is a raised design of mayapples. Fear to touch another whose metal is as thin as a hummingbird's wing.

All of this and no storefront, no pallets of cartons to be shipped, no telephones in a sales office or fibre connections receiving orders. Yet so many clamor to receive their spoons, without which they cannot sleep. Each night the factory floor is emptied and every morning new spoons unlike the last start filling it again, one at a time.

—Richard Magahiz

Unveiling the Moon

At the exhibition, we sip from fancy straws,

chatter through our coms

all the best gossip from in-gravity,

until the work is revealed.The moon floats free from its moorings.

We watch, entranced.The sculptor has outdone herself,

casting a moon of such colors and patterns.

Lines of frozen gasses trace an unknown script

across the surface.

Lakes of some substance she does not reveal

punctuate the lines, break the moon

into paragraphs and scenes.It tells a tale as it begins to spin into orbit.

Its gravity draws our eyes to the beautiful construct,

and we imagine a thousand and one stories

for every lake-cut line of lunar text.The artist flows above us, in a false atmosphere

basking in our admiration; and in the light of stars

that makes her sculpture glow.—Daniel Ausema

The Woman Out of Space by R. Pickman

You gaped at the pastel badlands, I at the oil deadlands:

A yellow field of grain on a winter's day,

pearl water in a well, red moss on the heath.

Where color touched color I drove myself wild.

There was a woman that was both opal and beautiful,

in her eyes the hues of myriad violence. Violence

both mundane and out of space, haunting me

with her foot about to fall, but never …—Amelia Gorman

Apocalypse Women

I touch a spot on the scroll and a glassy sphere

bubbles up. Three more, and the spheres rise

and spin, crinkling like distant xylophones.Gray clouds roll away, revealing giant redwoods.

Red and blue feathers dart between branches

and a porcupine trundles toward a clean, cold brook.I show my roommates the rainbow arch

of the space station. The library dome, a museum,

a concert hall. The bubbles? They fly,taking us to other places. Is this magic?

All of this was real. My grandmother

painted from memory.It’s so beautiful! The young girl begins to cry.

Two older women grasp their hands, amazed.

If one of us has a chance to escape …take this scroll and show the world

what we once knew and treasured.

We nodded, but we knew it was unlikely.A month ago, when cops and bots tore down

my door, I tucked the scroll inside my shirt

and left all else behind.The Women’s Traitor Detention Facility.

Four bunks in a metal shed. Labor duties

and nicknames. Squat. Mouth. Flaky.They call me Strange.

Each night we explore the scroll.

Each day we might be shot.

Anodized Titanium

Each night, after closing,

the curator views it againanodized titanium, untitled

accession number 2127.15.01depicting, of all things,

a lopsided baby elephantin garish soap-bubble hues:

magenta ears, blue trunksingularly unprepossessing,

notable only for its provenancedonated by the alien ambassador

a month before their attackthat history drawing crowds

the museum has never knownignorant, curious gawkers

whom the curator disdainsand, which gives her pause,

the human soldiers of the warhalting, unsure, awkward

looking out from inwardnessat accession number 2127.15.01

as if it meant somethingmany of the veterans returning

day after day, waiting in linefor their allotted minutes

before the gaudy elephantuntil the curator had reserved

Thursday viewings for veteranspermitted them the liberty

of touching the artworkthe diffidence of their fingers

striking the curator like lightningso that she comes each night

to study number 2127.15.01wondering what they see

when they look at it.

“More Tightly Raging Aggregates of Void”

(Recent Kinetic Pigment Works in Review)Three bridges stride a Heaven-Hell, oversoaring

dissolved horizons, unwilled. And as unwanted,

dispossessed emblazons snatching deftly up the sky

pierce the lie of a land’s end’s verisimilitude.

_ _ _Bleary shorn-in-shrivels of a glow exhaust heap up,

tumbling down pick-me-ups, rising in their tens and twos.

Empty? Certainly. Undone? – über-unearthly, plüs-alienated,

wholly clueless, aimless, useless… but on point.

_ _ _Shimmying off amorphous all-and-sundry scintillations

through which they entice the transverse eye to implore

well-rounded joys, straining, shapeshifting, endraped –

an inviting youthful hybrid tribe strips naked in hot energy.

_ _ _“Spectral transports stratify uncommonweal aesthetics

to totalify our vision and re-perceive us astride the now.”—David Jalajel

Most highly honored

Figure VII: The native-hatched sapiomorphs of Dome VI on Iapetus and their metalwork that blossoms into life at a touch, pinions swinging in low slung arcs to partition space herself into astonishing noble forms—now a hearthstone, now a flask of light, and in one case an engine of death. From each artisan is born a single master work, part child and the rest theorem, the greatest contemplated over Iapetan cycles by ticking scholars too dull to produce their own craft. Like cognitive giants the creators loom, more relentless than a glowing comet-fall, their secret methods secured in dusty tungsten urns.

Self-Portrait with Gorgons

Among the poison beauty of flax-leaved daphne,

where the flowers’ dreamless heads, nod darkly in the shade,

the face of some dead queen floats; pale in a carved niche,

of her own making, in the avenues of rosemary,

rue, and oleander; beneath cypress, cedar, and ancient yew.Once, she decorated these miles of pleasant tombs

with gods and kings, minotaurs and heroes; immortalised.

She needs no chisel to release an imprisoned satyr

from a marble block. Her sisters say, “she has a special

gift for it; this craft of portraying life in stone.”A smile of her garnet lips and a wink of her coal-black eye

memorializes the flesh. She imagines Athenians

coiled like ammonites, Trojans curled like trilobites,

Spartans shut tight like cockles, mussels, oysters, clams,

petrified among the ancient urchins and sharks’ teeth.She likes these gardens beneath the Mediterranean-blue

of the sky. Her hair coils in the foliage; luxuriant,

dense, darkly green. Medusa smiles under a bloody sun

setting hard in golden flames. She lifts a mirror

to her reflected gaze; in her face the stone is creeping.

In the Gallery of Queens

Wrapped in canvas, soul-stretched

embossed, the painted eyes of monarchs

dip into spaces between lucid dreams,

alien landscapes, their gaze a fixed

constellation bringing colonies

to their knees—We fall into cosmic outlines,

swim in the depth of their jaws, the ruins

of nations a neon shower of bonemeal

and ash, the bloodlust of bleeding women

a portrait of flesh-colored war hiding

in the corner of their eyes.Together they choke us with the madness

of burnt planets, suffer our mourning

beneath mountains of red moons,

their hands stained static with ambient

screams, the airglow a night without

promise of tomorrow—We bow to star-studded wounds,

pledge fear to a lineage of lost cities, swear

death to drowned kings, our allegiance

bound to the framed voices of tentacled

nightmares, each mouth screaming for

a reign of woman, queen.—Stephanie M. Wytovich

faerie folk

captured in haiga

iron gall ink—Mariel Herbert